The Wolf Man: Qualitative and Quantitative Multiplicities

How should psychoanalysis treat ambiguous numbers?

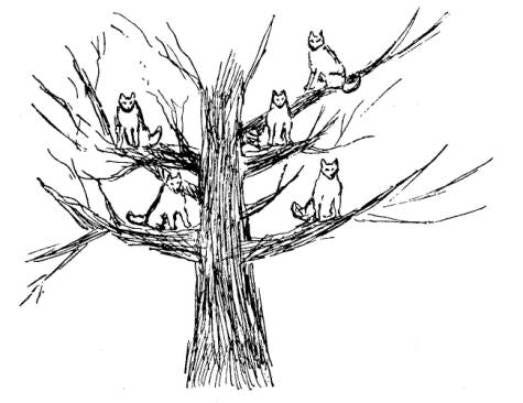

I dreamt that it was night and that I was lying in my bed… Suddenly the window opened of its own accord, and I was terrified to see that some white wolves were sitting on the big walnut tree in front of the window. There were six or seven of them.

This is from Freud’s paraphrasing of the Wolf Man’s dream. What begins as an indefinite determiner—“some” wolves—becomes specified further: there are “six or seven.”

In Freud’s interpretation, the numbers six and seven are grafted from a Grimm fairy tale, “The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats.” Seven goats become seven wolves, or maybe six, because in the story, one goat escapes and only six are gobbled up.

Whether there are some, six, or seven, Freud views the multiplicity of wolves as a resistant distortion of the repressed primal scene: two parents engaged in “coitus more ferarum.” We can imagine the Wolf Man’s logic as follows: There are at least two wolves. I’m not sure how many, but picking a number that is more than two gets me further away from having to confront the traumatic kernel that is at the center of my neurotic complex.

All well and good. But curiously, when the Wolf Man draws his dream, only five wolves make it onto the page.

If the multitude of wolves is meant as a distortion of two parents, and six and seven are borrowed from a fairy tale, then where does five enter the equation?

Freud is not content to leave the question of numbering alone. The illustrated five is “meant to correct the statement ‘It was night’” at the beginning of the dream. The Wolf Man witnessed the primal scene at 5pm, when he woke up from a feverish Malarial nap in his parents’ room.

Five wolves means 5 o’clock. It seems like a stretch, although Freud points out that the Wolf Man, throughout his life, experienced intense bouts of depression at 5pm, like clockwork. What’s more, a free association about his fear of butterflies reveals that he has associated the shape of butterfly wings with a “woman opening her legs” and the Roman numeral V.

But is this inconsistency—some, five, six, or seven—even worth pondering? Perhaps dream logic suspends the importance of discrete and countable entities. In this light, all that really matters is that there are multiple wolves.

This is the view taken by Deleuze and Guattari in their 1980 re-reading of the dream, found in chapter two of A Thousand Plateaus.

Who is ignorant of the fact that wolves travel in packs? Only Freud. Every child knows it… The wolves will have to be purged of their multiplicity… Freud only knows the Oedipalized wolf or dog, the castrated-castrating daddy-wolf, the dog in the kennel, the analyst’s bow-wow.

In Deleuze and Guattari’s account, the most salient characteristic of wolves is that they travel in packs. A pack of wolves is not a quantitative, but a qualitative multiplicity, a term we can borrow from Henri Bergson. Quantitative multiplicities are countable; qualitative multiplicities are n+1, more than one but not reducible to a set of singular entities. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

In this light, counting the wolves is a ridiculous endeavor. Clearly, we are not dealing with five, six, or seven, but with a pack, and any specific number would be arbitrary. A fair enough point. The scientism of Freud’s dream analysis led him to some truly ludicrous interpretations.

But I’m still unsatisfied by an account that effaces the importance of quantitative reasoning, especially with a patient like the Wolf Man who demonstrated an immense tendency towards anality.

Might it be possible here to treat Freud like Lacan does—a semiotician avant la lettre?

We can say confidently that five is a sign uniting a sound-image (“F-I-V-E” or “5”) with a concept (there being five of something). And even if numbers have no ontological status divorced from a set of material items they describe, we sure like to pretend to children that this is not the case. Western hylomorphism treats numbers is if they had an existence separate from that which they describe. In picture books, numbers dance around magically, conversing with each other on a plane of pure transcendence. The global economy peddles in abstractions of exactly this variety.

The truly Deleuzoguattarian picture book would be, of course, Where the Wild Things Are, the island being a perfect example of a body without organs, a plane upon which qualitative multiplicities pass.

But this is a transgressive exception. With most children’s books and stories we can ask questions like: How many dwarves? How many piggies? How many red fish and blue fish?

In a regressive scene like that of the Wolf Man’s dream, why would we ignore the importance of the number qua signifier? Deleuze and Guattari probably never heard the old joke “Why was six afraid of seven?”